What do I think of the EU minimum wage

Giuliano Cazzola's analysis of the EU minimum wage

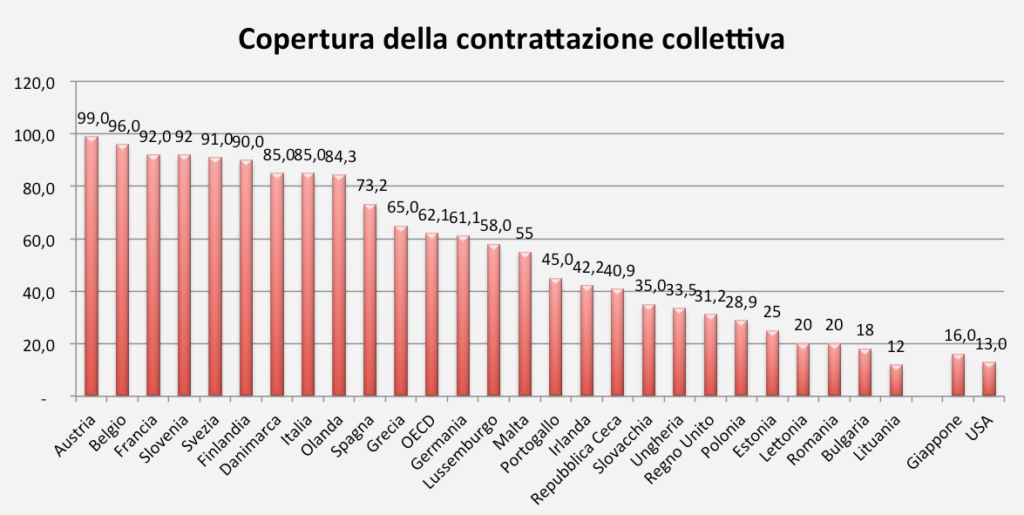

“The proposal for a European directive on wage adequacy, the first Union intervention directly concerning the subject of the minimum wage, marks a change of course, after European recommendations in this direction had multiplied for years“. This was stated by Tiziano Treu, president of CNEL , during a hearing at the 14th European Union Politics Commission in the Senate on the “Proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on adequate minimum wages in the European Union”. "The substantially positive opinion of the European trade unions, also confirmed by the major Italian confederations, is motivated above all by the preference recognized by the proposal to the contractual way over the legislative one for the setting of minimum wages". The social partners also underline the need to consider the "greater representativeness" of the stipulating organizations ”, added President Treu. In fact, the EU proposal explicitly states that “the protection guaranteed by the minimum wage can be provided through collective agreements, as happens in six Member States, or through statutory minimum wages, as happens in 21 Member States”. Minimum wages, while increasing in recent years, remain too low compared to other wages or to ensure a decent life in most Member States where national statutory minimum wages are provided. National statutory minimum wages – continues the EU – are less than 60% of the median gross wage and / or 50% of the average gross wage in almost all Member States. In nine Member States in 2018, the statutory minimum wage did not constitute sufficient income for an individual earning worker to reach the at-risk-of-poverty threshold. In addition, some specific groups of workers are excluded from the protection afforded by national statutory minimum wages. Member States with a high coverage of collective bargaining – the proposed directive points out – tend to have a low percentage of low-wage workers and high minimum wages. However, even in Member States that only use collective bargaining some workers do not have access to the protection afforded by the minimum wage. The percentage of uncovered workers ranges from 10 to 20% in four countries and reaches 55% in a fifth country.

As Silvia Spattini recalled in the Adapt Bulletin n. 34/2020 “the countries in which there is a legal minimum wage , with very few exceptions (Belgium and France), have a bargaining coverage of less than 80% of workers; on the other hand, countries without a legal minimum wage have coverage rates above 80% (except Cyprus). The same proposal for a directive underlines that Member States with a collective bargaining coverage rate of more than 70% show a lower percentage of low-wage workers ”. The proposal is undoubtedly important because it indicates a greater interest of the EU in the economic and social effects produced by the counter measures and assumes in the context of a resilience strategy also the confirmation and consolidation of an adequate wage policy, moreover in a phase in which, in Italy, the renewals of national contracts are underway, the level of negotiation dedicated precisely to safeguarding minimum wages.

In practice, the Italian model can no longer be referred to as the one that does not provide for a legal minimum wage unlike other 21 European countries and is therefore "in compliance with the trade unions" (as it was once said) if the legislative intervention is limited to provide sufficient wage coverage (as required by both Law 92 of 2012 and the Jobs Act of 2014) to sectors excluded from the structural system of collective bargaining. Having one's own specificity recognized can serve on a political level, but it does not solve the problems on which the legislative process launched in the Senate on the basic text first signed by Nunzia Catalfo, then president of the Labor Commission, got stuck. And this is precisely the crucial passage in the case of Italy, to avoid which – as Francesco Seghezzi and Michele Tiraboschi wrote in the Adapt Bulletin n. 44/2020 – there is no "shortcut": "The fact that the European Commission relaunches the issue with a directive, and not with simple recommendations, could be a further tool in the hands of the government that has never hidden its intention to move in this management, despite the opposition of the majority of the social partners. Not that the directive obliges us to go in the direction of a minimum wage established by law, nor does it impose, alternatively, to endow collective agreements with erga omnes effectiveness, perhaps with a law on representation in implementation of the precept referred to in Article 39 of the Constitution. . And yet this does not exclude initiatives in this sense ”. Italian trade union law – in essence – is once again grappling with a problem that has accompanied it since 1948 when the Republican Constitution came into force: how can erga omnes contractual rules stipulated on the basis of common law be applied? In Italy this result has been achieved for decades as a matter of fact and according to the jurisprudence in application of article 36 of the Constitution. But it was the first requirement (now shaky and undermined) to justify the second. It is therefore possible to find an itinerary that leads to recognizing the general effectiveness of the contracts stipulated by the historical trade unions, avoiding to submit to the Ghino di Tacco article 39 of the Constitution in a legal context whose meaning of article 19 of law no. 300/1970? Hic Rhodus hic salta: either this passage is located in the North West or it is difficult, even in Italy, to escape the halt of the legal minimum wage.

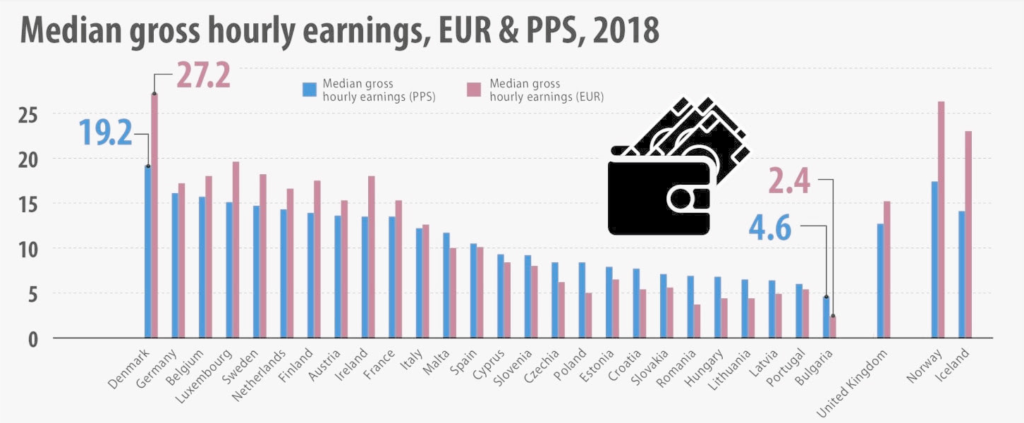

Then there are other aspects that it is time to take into consideration, starting with the differences in hourly wages in the EU countries, not in absolute terms, but with respect to their purchasing power. A Note from the Bruno Leoni Institute helps us. Measured in October 2018, the highest median gross hourly wages were recorded in Denmark (€ 27.2), ahead of Luxembourg (€ 19.6), Sweden (€ 18.2), Belgium and Ireland (18.0 € each), Finland (€ 17.5) and Germany (€ 17.2). In contrast, the lowest median gross hourly wage was recorded in Bulgaria (€ 2.4), followed by Romania (€ 3.7), Hungary and Lithuania (€ 4.4 each), Latvia (€ 4.9) , Poland (€ 5.0), Croatia and Portugal (€ 5.4 each) and Slovakia (€ 5.6). In other words, in the Member States, the highest national median gross hourly wage was 11 times higher than the lowest when expressed in euro. The median gross hourly wage varies from 1 to 4 between Member States when expressed in PPS (Purchasing Power Standard). In Member States, the highest national median gross hourly wage was 4 times higher than the lowest when expressed in purchasing power standards; which eliminates the differences in price levels between countries. As measured in October 2018, the highest average gross hourly earnings in PPS were recorded in Denmark (PPS 19.2), ahead of Germany (PPS 16.1), Belgium (PPS 15.7), Luxembourg (PPS 15, 1 PPS), Sweden (14.7 PPS) and the Netherlands (14.3 PPS). At the opposite end of the scale, the lowest median gross hourly wage was recorded in Bulgaria (PPS 4.6), followed by Portugal (PPS 6.0), Latvia (PPS 6.4), Lithuania (PPS 6.5 ), Hungary (PPS 6.8) and Romania (PPS 6.9).

This is a machine translation from Italian language of a post published on Start Magazine at the URL https://www.startmag.it/economia/che-cosa-penso-del-salario-minimo-ue/ on Sun, 27 Dec 2020 06:01:31 +0000.